Photo Sleuth

A human-AI collaborative platform for researching historical photos

This post summarizes my work on Photo Sleuth, an online platform dedicated to identifying historical portraits using a combination of AI and crowdsourcing. I am the lead developer and researcher on this project, which serves as the cornerstone of my PhD work with Dr. Kurt Luther at Virginia Tech.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Historical photo identification: Why do we care?

- TL;DR

- Background: Civil War Photography

- The Need for Human-AI Collaboration

- Civil War Photo Sleuth: The platform

- Mixed-Methods Evaluation

- Key Findings

- A Year Later

- Success Stories

- Takeaways

- Ethical Concerns

- Zooming Out: Future Plans and Vision

- Spotlight

- Publications

- Additional Readings

- Credits

Historical photo identification: Why do we care?

Identifying people in historical photos provides significant cultural and economic value. Whether it’s recognizing the contributions of marginalized groups, correcting historical records, or significantly increasing the market worth of undervalued images, historical photo identification has a powerful role in shaping our understanding and preservation of history.

This process draws the interest of various organizations such as GLAMs (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), and groups of individuals including historians, archivists, documentary filmmakers, journalists, genealogists, family history researchers, collectors, and dealers.

TL;DR

We created Photo Sleuth, a web-based platform that combines crowdsourced human expertise and automated face recognition to support portrait identifications from the American Civil War era (1861-65). Our mixed-methods evaluations of Photo Sleuth one month and 11 months after its public launch showed that it helped users successfully identify unknown portraits and provided a sustainable model for volunteer contribution. Over 20,000 registered users have uploaded 30,000+ photos to the platform since it was publicly launched on August 1st, 2018.

Background: Civil War Photography

The American Civil War (1861–65) was the first major conflict to be extensively documented through photographs. Photography was becoming popular around that time and people were taking photos for their loved ones. An estimated 3 million soldiers fought in the war and most of them had their photos taken at least once. After 150 years, millions of these portraits survive in museums, libraries, and individual collections, but the identities of most have been lost.

These photos have fostered a vibrant community of Civil War photography enthusiasts over time, which includes individuals exploring their family photos, collectors cherishing these historical artifacts, and re-enactors bringing past moments to life. This distributed community also has an active online presence where they leverage the wisdom of crowds for identifying unknown photos.

The Need for Human-AI Collaboration

Identifying historical photos is analogous to finding a needle in a haystack (I elaborate on different facets of this process in a separate post).

Challenges with current practices

- Task Complexity and Lack of Tech Support: Identification in historical photos is a complex process, and researchers lack adequate technological aid.

- Manual Practices: Historians, genealogists, archivists, collectors, and other experts primarily rely on manual, time-consuming methods for photo identification.

- Tedious Process with Uncertain Success: These manual methods involve navigating through low-quality photographs, military records, and reference books, a task that is not only tedious but also lacks any guarantee of success.

Double-edged AI to the rescue?

Automated facial recognition algorithms can support this effort of quickly sifting through thousands of images.

However, these algorithms are far from being perfect. Further, historical photographs add unique challenges, as they are often achromatic, low resolution, and faded or damaged, which may result in loss of useful information for identification.

So, what does this point to?

Charting out specific roles in this human-AI collaboration:

- Humans take the helm, guiding facial recognition technology on where to focus.

- Facial recognition does its thing—scouring through the database quickly to retrieve a set of visually similar photos.

- And, of course, the crucial last word on the decision? That rests with the humans! (Remember, algorithms are far from being perfect!)

This brings us to Photo Sleuth!

Civil War Photo Sleuth: The platform

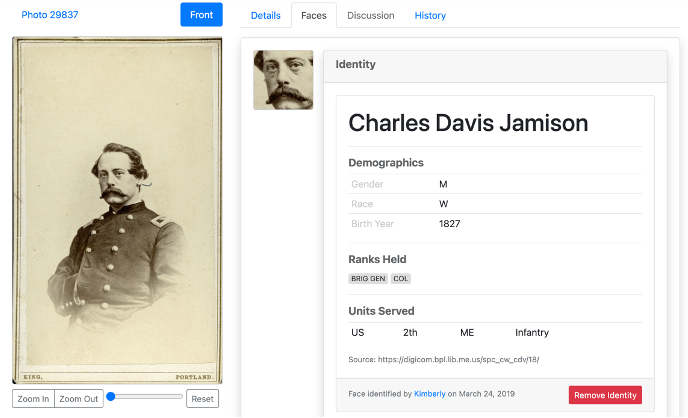

Photo Sleuth is an online platform we developed to identify unknown people in Civil War–era portraits. The website allows users to upload photos, tag them with visual clues, and connect them to profiles of Civil War soldiers with detailed records of military service.

Given that the task of person identification resembles the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack, we’ve modeled our person identification pipeline into three main components: (a) building the haystack, (b) narrowing down the haystack, and (c) finding the needle.

A. Building the Haystack

Photo Upload: The user uploads the portrait of the unknown Civil War soldier (front and back view, if available).

Face Detection: We use Microsoft Azure Face API to detect a face in the photo.

Visual Tags: The user looks for visual clues in the photo (e.g., uniforms, insignia) and tags them.

Metadata: The user tags the photo for metadata, such as original source, photo format, and inscriptions.

But…. how does Photo Sleuth’s first user get a match for the first photo they upload?

The Cold Start Problem: We initially seeded Photo Sleuth with ~20,000 Civil War soldier portraits from public sources such as the US Army Military History Institute, the US Library of Congress, and the US National Archives, as well as other private sources.

Bootstrapping, ownership, and network effects: Photo Sleuth adds the photo along with all the supplemental information into the reference database, irrespective of identification status, while displaying authorship credentials to the user. These photos enrich the database for potentially identifying future uploads.

B. Narrowing down the Haystack

Search Filters: Using the visual tags provided by the user, the system automatically generates search filters that map on to service records. For example, a “blue coat color” will map on to “Union Army”, or a “one bar in shoulder straps” will map on to “First Lieutenant”. These filters will narrow down the search pool from the entire database to a set of relevant candidates.

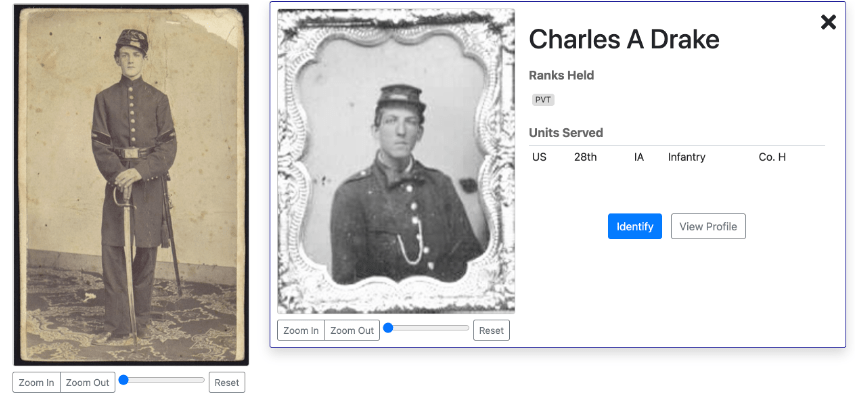

Facial Similarity: The search filters create a reduced search space in which facial recognition, powered by Microsoft Azure Face API, looks for similar-looking photos of the query image. The most similar-looking results, above a threshold of 0.50, are displayed on a search results page, ranked according to similarity to the query image.

C. Finding the Needle

User Review and Decision: Each search result shows the military service record highlighted next to the name and the face. The user closely inspects the facial recognition-retrieved similar-looking search results via a comparison interface. If they are confident about a match, they can go ahead and click the “Identify” button to link the query photo to the soldier’s profile and receive an “identifier” attribution.

But…. what if there are no matches in the search results and the user has prior information about the query photo’s identity?

The user can also add new names and service records to the database if that soldier profile has not yet been added. To prevent misinformation being spread and promote cross-verification, all users are required to follow the entire workflow, even for photos whose identities they believe they already know. In such cases, the user is asked to provide the source of identification.

We released Photo Sleuth to the public on August 1st, 2018.

Note: Many existing features have been modified since then (as we will see in subsequent projects such as DoubleCheck and PhotoSteward).

Mixed-Methods Evaluation

We were interested in understanding how well did Photo Sleuth support users in performing these three tasks: adding, tagging, and identifying photos.

We examined website logs and did an in-depth content analysis of all user-uploaded photos within the first month. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with nine Photo Sleuth active users in the first month. We followed up with a longitudinal study of Photo Sleuth after 11 months of its release.

Key Findings

Active user engagement observed in the first month with notable power contributors

Out of the 612 registered users, 182 users contributed by uploading at least one photo, resulting in a total of 2,012 photos (includes both front and back views).

Three power users uploaded more than 200 photos, and 11 users uploaded more than 30 photos each.

“I’m just trying to help other people out like I want me to be helped out.”

– P6 on why they wanted to contribute to the website

Users added both identified and unidentified photos to the platform

Users uploaded nearly equal numbers of identified and unidentified photos, illustrating a balanced participation in the platform’s main functionalities.

“I just uploaded to see if maybe there’s a collector out there that had

– P8 on what they were hoping out of uploading

the same image maybe of a different pose or a different backdrop, different uniform.”

If we consider only identified photos, 441 were pre-identified (i.e., their

identities were already known by the uploader), whereas 119 photos were post-identified (i.e., their identities were discovered using Photo Sleuth’s workflow).

“As your database of identified people increases, then there’s a greater [chance] …later on when I [upload] an unidentified image then I’ll get a hit, where if I do that today, my odds are much less.”

– P4 on why they were adding identified photos

Majority of users attributed sources when adding identified photos

While users were proactive in attributing sources while adding pre-identified photos, concerns were raised about potential unauthorized reuse, or ‘bootlegging’ of their contributed photos.

“I’m worried about putting them on there, only because I don’t want them using my stuff unless they get permission from me first.”

– P3 on why they did not want to add pre-identified photos

Despite these concerns, users still demonstrated good practice by providing attributions for most of their identified photos (90% of the pre-identified cases had a source attribution).

Photo tagging feature was extensively utilized by users for refining search results

Users had provided one or more tags for at least 401 of the 602 unidentified photos they added to the website. Out of the 560 identified photos (both pre-identified and post-identified) added by users, 445 photos had one or more tags associated with them. Further, 115 of the 182 users who uploaded photos also tagged a photo with at least one or more tags.

Uniform-specific tags, like ‘Coat Color’ and ‘Shoulder Straps’, were among the most commonly used tags, indicating users’ attention to visual details when analyzing photos.

Photo Sleuth’s search workflow assisted users in successfully identifying unknown photos

In the first month, 119 previously unidentified photos were matched to 88 existing soldier identities with a prior photo in the database. In some cases, more than one photo was matched to an identity.

“I started running that whole pile of images that I had trying to find IDs on ’em, and I wanna say I found maybe ten to fifteen percent hits on images that I had squirreled away, that [Photo Sleuth] were able to compare to and bring up either the exact same image or an alternative that was clearly the same person.”

– P5 describing their experience with Photo Sleuth’s search feature

Participants also favorably compared Photo Sleuth to traditional research methods.

“….saves a ton of time because now I don’t have to just go through every single picture that’s available …When I first get an image, that’s usually what I do—books, go online, search different areas, old auction houses …But I kind of don’t have to do that anymore because Photo Sleuth helps a lot.”

– P8 emphasizing the advantages of an AI-based search approach

For photo identification, users didn’t just rely on facial similarity. They also took into account inscriptions and military service records, indicating a holistic approach to photo identification.

“Without more information besides the face, I’m not gonna

– P9 on how confident they are about facial similarity

say it’s one hundred percent.”

Further, users also checked multiple search results carefully before confirming a match. The image below shows an example of search results where the top result is not the correct match. In fact, the user here correctly matched the photo to “Orlendo W Dimick”.

We also conducted an expert review of all the newly identified photos (119) and found that users were generally good at identifying photos using Photo Sleuth’s workflow (see Table below).

| Replica (Same Person, Same View) | No Replica (Same Person, Different View) | |

|---|---|---|

| Signed inscription of the name present in the photo | (Easiest) 17 positive matches | (Medium) 20 positive matches; 1 negative match |

| Signed inscription of the name absent in the photo | (Medium) 13 positive matches | (Hardest) 25 positive matches; 12 negative matches |

A Year Later

Photo Sleuth’s workflow offered a sustainable model of volunteer contribution. Over the next 11 months, we saw that over 12,000 users had registered on the website.

Over 1600 users had contributed at least one photo, with six power users who had uploaded more than 100 photos each. The number of user-uploaded photos at the end of 11 months was over 7000.

Photo Sleuth currently has over 20,000 registered users and 51,000+ photos. (2013)

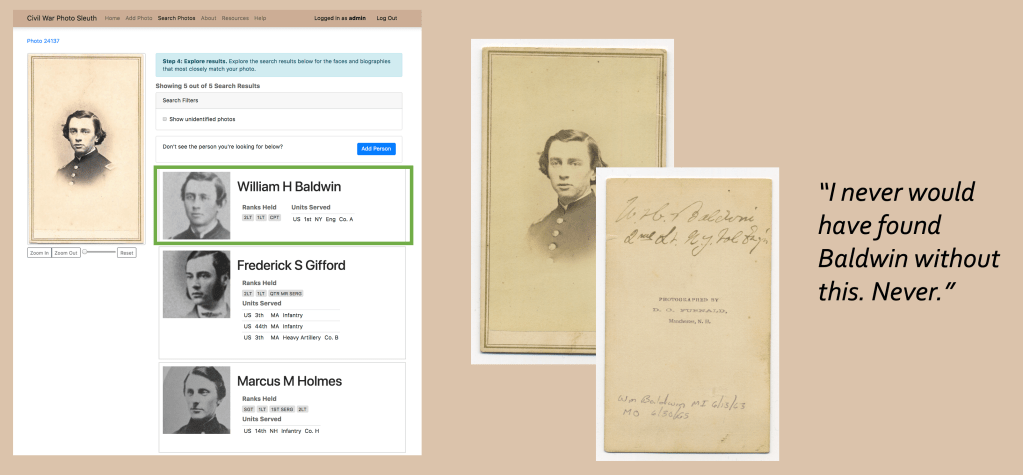

Success Stories

Photo Sleuth has made many new identifications possible in both private and public collections.

Takeaways

- Photo Sleuth’s design decisions fostered original historical research, promoted accuracy and limited the spread of misinformation.

- Photo Sleuth’s person identification pipeline helped create a sustainable model for volunteer contribution.

- Photo Sleuth’s crowd-AI pipeline has broader implications for modern person identification systems.

Ethical Concerns

Facial recognition technology, while innovative and powerful, has garnered concerns due to its well-documented biases and misuse, particularly in law enforcement scenarios. Instances of gender and racial bias, false positives leading to wrongful arrests, and breaches of privacy rights spotlight the need for greater scrutiny, accuracy, and ethical considerations.

While the time period (US in the 1860s) avoids many contemporary privacy-related issues for Photo Sleuth, the use of facial recognition still raises concerns around how accurate the search feature is for African American photos or how disproportionate the database is when it comes to race and gender. We have explored these ethical concerns in a subsequent project: Civil War Twin and in our AIES paper.

Photo Sleuth’s open participation model coupled with facial recognition technology does come with its potential risks, as concerns have been raised about the possibility of amplifying historical misidentifications as the platform expands. To mitigate this, we have introduced and continue to enhance features such as DoubleCheck and PhotoSteward. We have designed these features to ensure a higher degree of accuracy and validation, and safeguarding the integrity of our growing historical repository.

Zooming Out: Future Plans and Vision

The Photo Sleuth community has been active for almost 5 years and engages in photo investigations by collaborating with other users and AI tools. This platform opens up the doors for a lot of interesting research questions around crowdsourcing, online communities and human-AI collaboration.

I will be talking more about this in future blog posts. Please feel free to reach out if you have interesting ideas to discuss!

Spotlight

Photo Sleuth has received numerous awards over the years

- Grand Prize of $25,000, Microsoft Cloud AI Research Challenge

- Best Paper award at ACM IUI 2019

- Best Poster award at AAAI HCOMP 2018

- 2nd Runner Up, Best DH Tool or Suite of Tools, Digital Humanities Awards 2018

Photo Sleuth has also received major press coverage, including Smithsonian, TIME, Popular Mechanics, Slate, and the History Channel.

Publications

Photo Sleuth: Combining Human Expertise and Face Recognition to Identify Historical Portraits.

V. Mohanty, D. Thames, S. Mehta, and K. Luther.

ACM Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces (IUI 2019), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. (25% acceptance rate)

🏆 Best Paper

Photo Sleuth: Identifying Historical Portraits with Face Recognition and Crowdsourcing.

V. Mohanty, D. Thames, S. Mehta, and K. Luther.

ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems (TiiS), 10(4), 1-36 (Invited Submission)

Supporting Historical Photo Identification with Face Recognition and Crowdsourced Human Expertise.

V. Mohanty, D. Thames, S. Mehta, and K. Luther.

Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence Sister Conferences Best Papers. Pages 4755-4759 (Invited Submission).

Extended Abstract

[Link to Video]

Photo Sleuth: Combining Collective Intelligence and Computer Vision to Identify Historical Portraits.

V. Mohanty, D. Thames, and K. Luther.

ACM Conference on Collective Intelligence (CI 2018), Zurich, Switzerland, 2018. (32% acceptance rate for oral presentations)

Additional Readings

- Check out Kurt Luther’s amazing photo sleuthing stories in Military Images!

Credits

Special thanks to Ron Coddington, Paul Quigley, Nam Nguyen, Abby Jetmundsen, Ryan Russell, Natalie Robinson, Sneha Mehta, David Thames, Liling Yuan, Manisha Kusuma, Chanaka Perera, Jude Lim, Terryl Dodson, Kareem Abdol-Hamid, Courtney Ebersohl, and the wonderful Photo Sleuth users!

This research was supported by NSF IIS-1651969 and IIS-1527453 and a Virginia Tech ICTAS Junior Faculty Award.